A Baby Who Is Just Like Me

When biology failed, a foster agency delivered the perfect baby to us

When I look at my baby girl’s face, I see myself. She’s a mutt like me, with many ethnicities swimming around in her gene pool. She has my dark, wavy hair, full lips, and chunky thighs. And, like me, she laughs easily and often. Her nose, though, looks like her dad’s. And her skin tone is a mix of ours – my olive undertones blended with his café au lait coloring. Everyone says she looks like a perfect combination of the two of us. Which is odd, because she came from our local foster agency. Also like me, she is adopted – well, almost.

My husband and I had been trying to adopt for three years when we got the social worker’s call. Only a week before, we had finally completed all the required steps: fingerprints, FBI background checks, confessions of underage drinking arrests in college, approximately 24 hours of meetings with a social worker (who inquired how often we have sex), and a two-month, state-run training to become certified foster parents. We were prepared to wait another year or more. But the call came right away: A 4-day-old baby girl was waiting at the hospital. Did we want to bring her home? Such a simple question after such a long process.

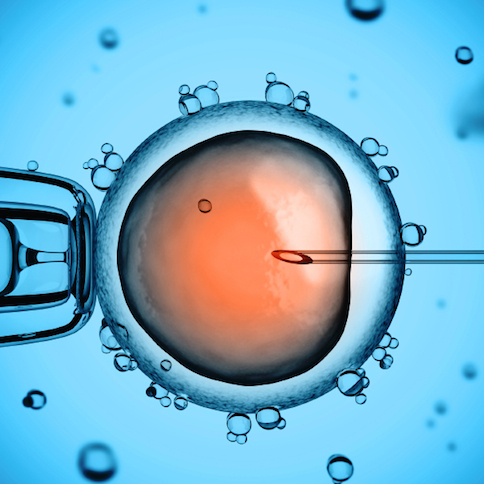

My husband and I married when I was 36, and two years later I started IVF treatments. Despite the less than stellar success rate, I assumed it would work for me. (After all, tabloids are full of pregnant celebrities in their mid- to late 40s.) But it only produced three embryos, and none of them cozied up in my uterus for a 9-month stay. I gave up at the age of 41 when one fertility doctor told me that IVF was increasing my chances of getting pregnant by about 1 to 2 percent. (Turns out most of those celebrities use donor eggs from much younger women.)

I tried so hard to have a baby who shares my DNA because I don’t know anyone who does. But I also wanted to adopt. I know what it is to love an adoptive mother and to be loved by one just as much as if she had given birth to me. My husband and I had hoped to do both. But my biology had other plans, so we moved on.

Price shopping for babies

We ruled out international adoption because some parents told me they chose that route to reduce chances the birth parents would ever resurface. As an adopted person curious about her genetic past but unable to find her birth family, that was not a plus for me. And international adoptions take longer than ever – several years in many cases. Some countries are even halting them altogether.

So we settled on a private domestic agency, gave them a down payment, and received our first email: “Due date: October 15; Mother: Caucasian; Father: one-quarter African American, three-quarters Hispanic. Possible, but minimal, drug exposure; Estimated cost: $20,000. “

Soon others came that read more like this: “Due Date: August 23; Mother: Caucasian; Father: Caucasian; No drug exposure; Estimated cost: $40,000.”

No regulatory agencies oversee the private adoption process, so the laws of supply and demand control how much you pay. Babies of color were literally half the price of more expensive white babies.

We didn’t care what color our baby was, so we were tempted to go with one of the “bargain” babies. But no matter how much one adoption lawyer argued with me that it wasn’t like buying a baby, it really was. And that made us uncomfortable.

We knew of families who had gone through the foster system (“fost-adopt” as it’s called in the industry) and had good experiences. No money is involved except for the monthly stipend foster parents receive from the state. But it still carries risks, especially when you’re talking about a baby: Parents whose children have been removed from them can get back on track, and extended family members can come forward and receive priority if they show they can offer the child a loving, stable home. Just the possibility of those events can draw out the time between falling in love with your foster child and the time she might become your own.

But adopting through foster eliminated the feeling that we were participating in a baby marketplace. And I had been a foster child in Pennsylvania for three months before being adopted, so it seemed right.

Getting the call

We were giddy and terrified. We hesitated. The social worker emphasized the risks – we might lose her, she may have been exposed to drugs, it was possible she could be HIV positive – but she also said this: “No matter what, you will be helping this newborn baby. She has nowhere else to go right now.”

That’s why we drove to the hospital that afternoon. What a privilege to have the opportunity and ability to give safe haven to a newborn baby for any amount of time.

During our foster training, we learned about how hard we’d have to work to develop an attachment with our child if he or she were a little older. We imagined bringing home a 2- or 3-year-old and joked that we would “get lucky” and skip the sleepless nights and colic that came with newborn care. Now that she’s 6 months old, I can’t express how grateful I am that we didn’t miss one second of the intense sleep deprivation. We did get lucky.

That first night, I tried to prepare myself for the worst – not being able to keep her. I told myself to “be realistic,” “keep your distance emotionally,” and “not get too attached.” That resolve lasted approximately the time it took to form the thought. From that point on, I was a goner. And I’m further gone with every diaper change, spit up in my hair, and impossibly happy smile and giggle from this beautiful baby who looks just like us. There are hurdles still to clear, but no matter what happens, I will have no regrets.