From Dashed Dreams to a Donor Egg

How a genetic disorder changed my path to motherhood

t has been more than five years since the first time I got pregnant. So much has happened and so many questions remain unanswered. The top geneticists and perinatologists in the country have tried to make sense of our case. They can’t figure out what’s wrong, but I’ve figured out that it’s rarely a good thing when you become “a case.”

I have one child. He just turned 4 years old, and he is a ray of light who, for the most part, outshines the darkness. Nothing can completely erase the darkness because the pregnancy losses we’ve endured are experiences that have changed us forever.

Let me get you up to speed on my reproductive history:

- First pregnancy: miscarriage, 8 weeks (cause unknown)

- Second pregnancy: late loss, 20 weeks (recessive genetic condition)

- Third pregnancy: full-term pregnancy, healthy baby boy!

- Fourth pregnancy: second late loss, 20 weeks (recessive genetic condition)

- Fifth pregnancy: miscarriage, 9 weeks (likely age-related)

After the first late loss, the doctors assured us that it was a fluke, a one-time chromosomal accident. Exactly a year later, the arrival of our baby and the joys of parenting made our loss a bit less senseless and a lot less agonizing. Balance and justice had been partially restored.

When our son was a year and a half, I got pregnant again. A CVS at 11 weeks foretold a healthy, baby girl. But 8 weeks later, our doctor broke the news at a routine ultrasound: Like our second pregnancy, she had an abnormally shaped brain that did not function. We knew from the previous experience that there was no hope.

At that moment, I lost my mind. Perhaps I left it in the world that I had inhabited just 20 minutes before I heard the news, but from which I had suddenly been exiled. That hideous scene has replayed in my mind countless times since that fateful day.

The new normal

Now, I look back to my one successful pregnancy with a sense of nostalgia and wonder: ‘Will I ever get that far again? Was that my last time giving birth?’ If only I could concoct a formula for healthy-baby-making and apply it to the present.

But my husband and I share a recessive genetic condition that has no name, no syndrome to attach to it or gene associated with it. With recessive genetic conditions, the chance that any fetus will be affected is only 25 percent. With those chances and five pregnancies under our belt, we should have at least two children (which is still our hope).

But we’ve learned the hard way that the universe does not care about fairness. It was our simple, horrendous luck that our odds came in at more than 25 percent. There was nothing we could do to change that. And there’s nothing we can do to plan for or avoid it in the future. The stats and the doctors’ diagnoses fail to matter now.

What does matter is that I have managed to get through it. My marriage has not only survived, but is stronger (with the help of a great therapist). And, for the most part, I am a happy and fortunate person with so much still to experience and enjoy. People who have helped me through this trial have allowed me to see that my strength is formidable and something I should take pride in. I do, and it is one of the many tools that get me through the hard days.

Our struggle has compelled me to focus on what I do have and to be as present as I can with my son who is alive and thriving. I can’t afford to linger in my losses. The sadness still punctuates and colors my experience, but only rarely does it manage to consume me like it used to. I let it come, hang around for a bit, and then I ask it to move on so I can continue to play pirates with my kid.

Going with a donor egg

The losses and the unknowns of our case are all part of our story. I don’t have to like that part of the story, but I try to let it inform my choices now. After the last miscarriage, we finally decided we’d had enough. We are not ready to give up on having a second child, but we are willing to let go of the hope of having another fully biological child.

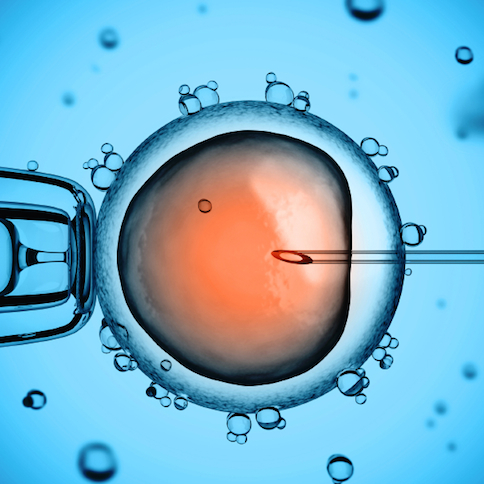

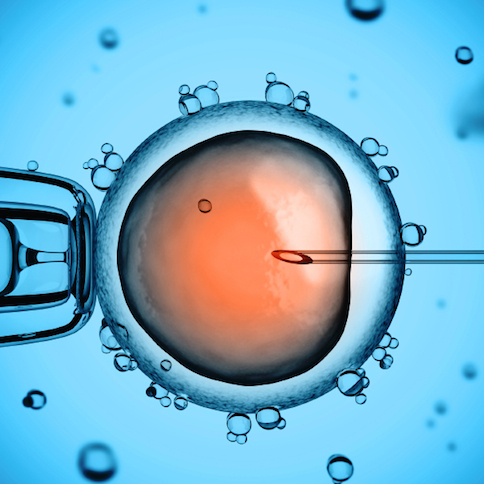

If we knock out one of our gene pools, then we eliminate the genetic problem. So we have decided to use an egg donor (mostly because we have a better chance of success with a younger woman’s eggs and my husband’s sperm, than with another man’s sperm and my more mature eggs).

I now need to add to my list of losses the sacrifice of never having my own genetic child again. But I choose that loss rather than another miscarriage or another nightmarish ultrasound at 20 weeks. The choice to move out of our comfort zone and rely on a third-party to expand our family feels less like an absolute loss than a means of protecting and preserving all we have built together, and our best shot at having a healthy baby in the not-too-distant future.

Redefining family

My son is a living reminder of how amazing it can be when everything works out the usual way, but also of what all this struggle has really been about: having the family we set out to have. From this perspective, going with a donor does not seem so strange. I would still be able to carry, deliver, and breastfeed the baby. He or she would still be a part of me, but in a different way than my first child, and I firmly believe a baby conceived this way will still feel like mine.

Just a year ago I would not have been ready to have IVF treatments or consider using a donor. It seemed like something other people did. But our previous experiences and the harsh reality of our genetic situation have helped us adapt and grow. It has called upon us to make a previously unacceptable option our own – something new and surprising to weave into our unconventional, but rich, family story. And no matter many how many times we have been knocked down, we remain excited for the next chapter.